Senate bollocks

In today’s Sun: the NDP, in self-denial

Tim – he’s in it for him

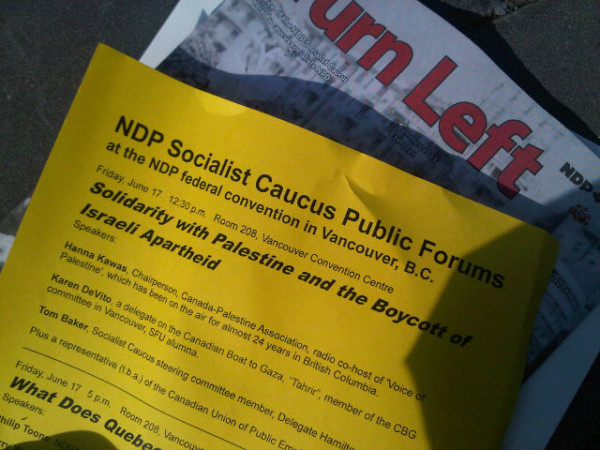

NDP links Israel to “apartheid”

This has been circulating today at the convention in Vancouver. A pity this wasn’t in circulation in Outremont during the federal election – but it’ll now be a question for Ontario NDP leader Andrea Horwath to answer, I expect. What a huge disappointment she (and they) have been.

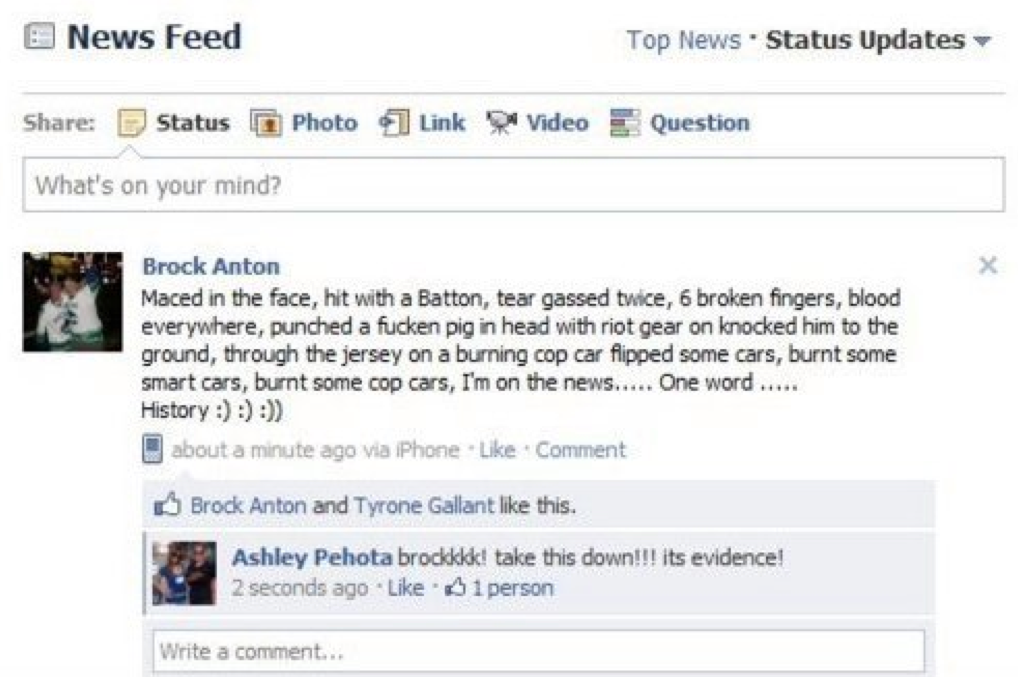

Enjoy the slammer, genius

On Hudak’s smear (updated)

Tonight, Hudak ran a ham-fisted attack ad during the final Canucks-Bruins game (and let’s not talk about “the game,” okay?). So someone sent me this in response. Looks like they did it some time ago, but I tend to think the criticism it contains – that Hudak’s in it for himself, not the taxpayer – will carry a bit more of a sting than the piece of sophomoric garbage he’s paying to put on-air.

It’s going to be an interesting campaign.

UPDATE: Best observation, from one of my fave sports columnists: “7 min.: Two things are now certain — Vancouver is going to have to do this 5-on-5; and Ontario Tory boss Tim Hudak’s big Game 7 TV ad splurge is wasted on the inebriated half of the audience and annoying the sober remainder.”

June 15

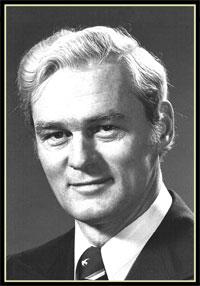

Dr. T. Douglas KINSELLA, CM, BA, MD, FACP, FRCPC.

Like some men, and as was the practice in some families, my brothers and I did not hug my father a lot. As we got older in places like Montreal, or Kingston, or Dallas or Calgary, we also did not tell him that we loved him as much as we did. With our artist Mom, there was always a lot of affection, to be sure; but in the case of my Dad, usually all that was exchanged with his four boys was a simple handshake, when it was time for hello or goodbye. It was just the way we did things.

There was, however, much to love about our father, and love him we did. He was, and remains, a giant in our lives – and he was a significant presence, too, for many of the patients whose lives he saved or bettered over the course a half-century of healing. We still cannot believe he is gone, with so little warning.

Thomas Douglas Kinsella was born on February, 15, 1932 in Montreal. His mother was a tiny but formidable force of nature named Mary; his father, a Northern Electric employee named Jimmy, was a stoic man whose parents came over from County Wexford, in Ireland. In their bustling homes, in and around Montreal’s Outremont, our father’s family comprised a younger sister, Juanita, and an older brother, Howard. Also there were assorted uncles – and foster siblings Bea, Ernie, Ellen and Jimmy.

When he was very young, Douglas was beset by rheumatic fever. Through his mother’s ministrations, Douglas beat back the potentially-crippling disease. But he was left with a burning desire to be a doctor.

Following a Jesuitical education at his beloved Loyola High School in Montreal, Douglas enrolled at Loyola College, and also joined the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps. It was around that time he met Lorna Emma Cleary, at a Montreal Legion dance in April 1950. She was 17 – a dark-haired, radiant beauty from the North End. He was 18 – and a handsome, aspiring medical student, destined for an officer’s rank and great things.

It was a love like you hear about, sometimes, but which you rarely see. Their love affair was to endure for 55 years – without an abatement in mutual love and respect.

On a hot, sunny day in June 1955, mid-way through his medical studies at McGill, Douglas and Lorna wed at Loyola Chapel. Then, three years after Douglas’ graduation from McGill with an MD, first son Warren was born.

In 1963, second son Kevin came along, while Douglas was a clinical fellow in rheumatism at the Royal Vic. Finally, son Lorne arrived in 1965, a few months before the young family moved to Dallas, Texas, to pursue a research fellowship. In the United States, Douglas’ belief in a liberal, publicly-funded health care system was greatly enhanced. So too his love of a tolerant, diverse Canada.

In 1968, Douglas and his family returned to Canada and an Assistant Professorship in Medicine at Queen’s University in Kingston. More than 35 years later, it was at Kingston General Hospital – in the very place where Douglas saved so many lives – that his own life would come to a painless end in the early hours of June 15, 2004, felled by a fast-moving lung cancer.

Kingston was followed in 1973 by a brief return to Montreal and a professorship at McGill. But an unstable political environment – and the promise of better research in prosperous Alberta – persuaded the family to journey West, to Calgary.

There Lorna and Douglas would happily remain for 25 years, raising three sons – and providing legal guardianship to grandson Troy, who was born in 1982. At the University of Calgary, and at Foothills Hospital, Douglas would achieve distinction for his work in rheumatology, immunology and – later – medical bioethics.

He raised his boys with one rule, which all remember, but none observed as closely as he did: “Love people, and be honest.” His commitment to ethics, and healing – and his love and honesty, perhaps – resulted in him being named a Member of the Order of Canada in 1995.

On the day that the letter arrived, bearing Governor-General Romeo LeBlanc’s vice-regal seal, Douglas came home from work early – an unprecedented occurence – to tell Lorna. It was the first time I can remember seeing him cry.

As I write this, I am in a chair beside my father’s bed in a tiny hospital room in Kingston, Ont.,where he and my mother returned in 2001 to retire. It is night, and he has finally fallen asleep.

My father will die in the next day or so, here in the very place where he saved lives. He has firmly but politely declined offers of special treatment – or even a room with a nicer view of Lake Ontario.

Before he fell asleep, tonight, I asked him if he was ready. “I am ready,” he said. “I am ready.”

When I leave him, tonight, this is what I will say to him, quietly: “We all love you, Daddy. We all love you forever.”

[Warren Kinsella is Douglas Kinsella’s eldest son. His father died two nights later.]

[From Globe’s Lives Lived, June 15, 2004.]

The Hatepinks

The subtlety and nuance of Should I Kill Myself or Go Jogging, from France’s finest punk combo.

1968 – Smoke or Fire

Holy God, I love this band, this song. Vid here. Words:

Young men sent overseas, their names are in a lottery that kills.

There are social clashes, body counts, and rioting on TV screens.

A bullet put another Kennedy to sleep.

Cover your eyes: You think America’s recovered from the self-inflicted wounds it took in 1968?

Still Corretta led his people through the Memphis streets,

In spite of the nightmare that was made out of a dream.