My latest in the Sun: pandemic politics for poltroons

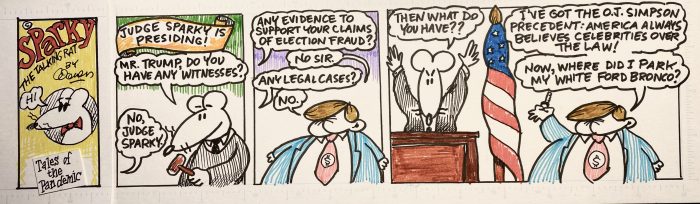

Donald Trump: you’re fired.

And Joe Biden didn’t fire you. The coronavirus did.

By voting day, Nov. 3, nearly 60% of Americans disapproved — or strongly disapproved — of Trump’s handling of the pandemic that is killing about a thousand of them every single day.

Ask any political consultant: when that many voters disapprove of what you are doing, you’re toast.

It wasn’t always that way for Trump. Way back at the start of the pandemic, Americans supported his leadership. At the end of March, in fact, when it felt like the world just might be ending, Trump’s performance was approved of by a narrow majority of Americans, said polling aggregator FiveThirtyEight.

That all changed on or about the first week of April. That was the week that U.S. COVID-19 deaths surged past the symbolic number of 10,000. After that, Trump was never again seen as handling the pandemic well. From July onward, the U.S. President’s performance rating remained constant: 60% of Americans were unhappy or very unhappy with him.

In those circumstances, Joe Biden essentially needed to maintain a pulse and smile a lot, which is what he did. His campaign, meanwhile, devoted itself to getting out the Democratic vote early — a process Trump mocked and attacked. It would prove to be a fatal mistake. Biden won mainly because of the support of those who voted early.

So, the pandemic can certainly end political careers, as it did for one Donald J. Trump. But elsewhere — in Canada, for instance — what effect does COVID-19 have on political outcomes?

Well, up here, there has not been a single incumbent government that has been defeated during the pandemic. Not one.

The minority NDP government in British Columbia was transformed into a majority, mid-pandemic. Same thing happened in New Brunswick: the minority Progressive Conservative government was elevated to a majority. In Saskatchewan, the Saskatchewan Party was re-elected, too — to its fourth consecutive majority government.

Federally, there hasn’t been a pandemic election, but Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was recently clearly tempted to engineer his own defeat.

In October, Trudeau refused to go along with Opposition demands to create a Parliamentary committee tasked with probing the propriety of government spending. Trudeau sent out his House Leader to state that the Liberal government considered the vote on the committee to be a confidence matter — meaning there would be an election if the government fell

It was absurd, it was ridiculous, it was unnecessary. It was also uniquely Canadian, too: only here — with our preoccupation with peace, order and good government — would a federal election be held over creating a committee!

If masked-up Canadians had trooped to the polls, would Trudeau have won? Yes. Ipsos pegged Trudeau’s support at six points above the Erin O’Toole’s Conservatives around the time of the committee contretemps. Abacus Data said the Liberal lead was as much as eight points.

Angus Reid found a smaller Grit advantage over the Tories — but two-thirds of Canadians, roughly, said that Trudeau’s government had handled the pandemic well. That figure has remained more or less constant since March, Angus Reid noted.

So what does it all mean? The polls don’t tell us that, exactly. But everyone accepts that the pandemic has massively disrupted our lives — politically, economically, socially, culturally. It is perhaps the biggest change most of us have ever faced as citizens.

That’s why incumbent governments are getting re-elected. Unless politicians have completely botched their response to the pandemic, voters are opting for the devils they know over the ones they don’t. They’ve quite enough disruption in their lives, thank you very much. They don’t want more.

Donald Trump is the exception. He made such a mess of his pandemic response, they couldn’t forgive him.

So they fired him.