Institutions, and why carding is illegal

I don’t detest the institution of the police. As with every other institution in society, it is an institution made up of good folks and bad folks.

So, my strong, strong objection to “carding” – the police practice of stopping individuals, without cause, to question them – doesn’t arise out of any hatred for the police. And I don’t object to carding simply because it is demonstrably racist, and because it tends to wrongly target young black men. I object to it because it is against the Constitution. Thus, I have written often about the issue, and I have even written a song about the arbitrariness of it all.

Kathleen Wynne’s decision to end carding is therefore welcome news. (I would have liked to see the announcement made somewhere in Scarborough Southwest before October 19, mind you, but at least it’s been made.) And it makes sense.

It makes sense, and has made sense, since 2009. Six years. What’s therefore amazing, to me, isn’t that carding was finally found to be unlawful – it’s that it has taken six years for the institution of government to acknowledge that.

In 2009, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled on R. v. Grant. Here are the facts, as penned by the high court itself:

“Three police officers were on patrol for the purposes of monitoring an area near schools with a history of student assaults, robberies, and drug offences. W and F were dressed in plainclothes and driving an unmarked car. G was in uniform and driving a marked police car. The accused, a young black man, was walking down a sidewalk when he came to the attention of W and F. As the two officers drove past, the accused stared at them, while at the same time fidgeting with his coat and pants in a way that aroused their suspicions. W and F suggested to G that he have a chat with the approaching accused to determine if there was any need for concern. G initiated an exchange with the accused, while standing on the sidewalk directly in his intended path. He asked him what was going on, and requested his name and address. At one point, the accused, behaving nervously, adjusted his jacket, which prompted the officer to ask him to keep his hands in front of him. After a brief period observing the exchange from their car, W and F approached the pair on the sidewalk, identified themselves to the accused as police officers by flashing their badges, and took up positions behind G, obstructing the way forward. G then asked the accused whether he had anything he should not have, to which he answered that he had “a small bag of weed” and a firearm. At this point, the officers arrested and searched the accused, seizing the marijuana and a loaded revolver. They advised him of his right to counsel and took him to the police station.”

Grant argued that his section 9 Charter rights – the right not to be arbitrarily detained or imprisoned – had been violated. Once his case wound its way through the system, the Supremes agreed. (Grant was black, by the by. Surprise, surprise.)

Wikipedia (uncharacteristically) has not-bad summary of the SCC decision in Grant, below:

“The majority found that “detention” refers to a suspension of an individual’s liberty interest by a significant physical or psychological restraint. Psychological detention is established either where the individual has a legal obligation to comply with the restrictive request or demand, or a reasonable person would conclude by reason of the state conduct that they had no choice but to comply.

In cases where there is physical restraint or legal obligation, it may not be clear whether a person has been detained. To determine whether the reasonable person in the individual’s circumstances would conclude the state had deprived them of the liberty of choice, the court may consider, inter alia, the following factors:

The circumstances giving rise to the encounter as would reasonably be perceived by the individual:

- whether the police were providing general assistance; maintaining general order; making general inquiries regarding a particular occurrence; or, singling out the individual for focused investigation.

- The nature of the police conduct, including the language used; the use of physical contact; the place where the interaction occurred; the presence of others; and the duration of the encounter.

- The particular characteristics or circumstances of the individual where relevant, including age; physical stature; minority status; level of sophistication.”

What our highest court is getting at, here, is that when the police stop a person, that person will almost always feel compelled to stop. And when the police ask that person questions, that person will almost always feel compelled to answer those questions, and not merely to be polite, either. “Psychologically,” to use the Supreme Court’s phrase, the person reasonably feels they have been “detained.”

So, too, in the case of carding. If a cop tries to stop a person to question them – a young black man, most of the time, but anyone else, too – the chances are exceedingly slim that that person will keep walking on by, cheerfully quoting the majority in R. v. Grant as they do so. No, the chances are that they will stop, and submit to the questions. The uniform, the pepper spray, the handcuffs and the gun have that effect on people.

Thus, my view. Carding isn’t now unconstitutional and therefore illegal – carding has pretty much always been unconstitutional and illegal.

All appearances to the contrary, we are a nation of laws. And it’s well past time that the institution of the police, and the institution of government, acknowledged as much.

Adler-Kinsellas Show! Refugees, judge-made law and Trudeau’s election promises

Listen in! And many thanks to Daryl Chomay, Pieter Dirk Dorsman, Tim White, Doug McComber and Robert Frindt for their donations for the web site and/or the radio show. If you want to hear/see more, use the handy-dandy donate button to the left, under the blogroll!

Advertisers, take note!

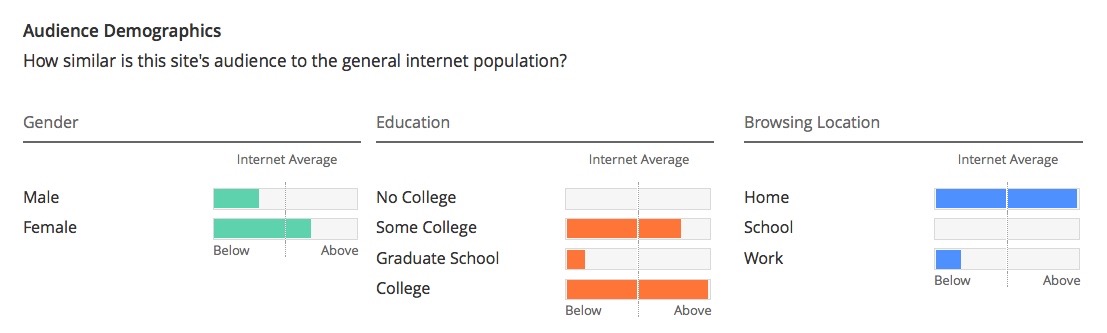

This little web site – celebrating Year Fifteen in a few weeks! – attracts more than 140,000 visits a month, with many more during election campaigns. I knew that.

What I didn’t know is what Alexa related to me this morning: the demographics of those who lurk here.

Given the predominance of male (or apparently male) commenters, I generally figured the broader readership skewed male, too. Apparently not.

Building imitates life

Owner cracked, too. @realDonaldTrump https://t.co/5ptKgoKEvV

— Warren Kinsella (@kinsellawarren) October 28, 2015

REMINDER: Bay-Adelaide remains closed. Trump Tower reported to have a cracked window. https://t.co/0j0tM0FfTt pic.twitter.com/KZQiwvVwNn

— CBC Toronto (@CBCToronto) October 28, 2015

Promises, promises

Prime Minister-to-be Justin Trudeau made not a few promises on the election trail, and he received a very clear mandate from Canadians to implement them. He said what he was going to do, and he is still giving every indication he is going to do what he said.

In many cases, the Liberal leader indicated an ambitious timeline for when these promises would be implemented. In most cases, he indicated real change would be coming within months, not years.

Thus, the unscientific poll below. Looking at it, you will see – as I did – that the new Liberal government has a very crowded legislative agenda looming on the horizon. Is it possible to do all of these things in the next few weeks? If you think so, say so in comments, and tell us how you would pull it off. If you think that one promise is more important that the others, say which one in the little online poll, below.

Whatever comes first, on one point we can all agree: real change is indeed coming.

In this week’s Hill Times: why the Liberals won, and why the CPC and NDP lost

What happened?

In politics, as in life, the simplest explanation — while beguiling — is not always the best one. So, too, was the interminable Canadian general election of 2015. No single thing can account for a change this big.

“Big” is the only way to describe what transpired during the nearly 80-day campaign, and its culmination on election night.

• When compared to 2011’s debacle, the Liberal Party of Canada increased its share of the vote by more than 4.1 million — an improvement of 60 per cent

• When also contrasted with 2011, the New Democratic Party shed nearly one million votes — a loss of almost 30 per cent support.

• There was an impressive and welcome improvement in voter turnout, which reached nearly 71 per cent — the highest it has been since 1993.

• Many, many seats changed hands, principally benefitting the Liberals — they took nearly 90 from the Conservatives, and almost 60 from the New Democrats.

In the House of Commons, the extent of the changes are seen most dramatically: the Conservatives have now assumed the spot held by the New Democrats, the New Democrats have been consigned to the lonely Commons perch once held by the Liberals — and, of course, the Liberals have vaulted to the lofty heights of government, and now sit where the Conservatives once did.

It all reflects what we saw during the writ and pre-writ period, with every one of the three main political parties having occupied the first, second or third spot in voters’ affections. For more than a year, Canadian voters were comparison-shopping, and moving around in a way that we had not seen before. At any given point, Harper, Trudeau, or Mulcair were considered the best choice for prime minister — and then summarily discarded.

Why?

As noted, while embracing a single, pithy explanation for it all is seductive, it probably isn’t the best way to approach an event as immense and as multifaceted as Election 2015. But a few observations can be made—three in particular, one for each of the parties.

1. The NDP: collapse

One million votes: that is what Thomas Mulcair lost from Jack Layton’s 2011 achievement. He lost those votes—and the NDP’s coveted official opposition role — for myriad reasons.

Chief among them: Mulcair did not win the debates. In an era where few voters still watch these televised contests, this should not have been fatal. But for Mulcair, it was: Ottawa-based journalists — the ones who still cling to the false notion that Question Period is relevant — were enthralled by the NDP leader’s prosecutorial style, and his ability to hold the government to account. They spared no glowing adjective, and predicted that Mulcair would win every debate. But he did not: his style was affected and condescending. He seemed phony.

Another problem: the NDP ran a low-bridge, frontrunner campaign when their frontrunner status was anything but certain. When an aspiring leader is always playing it safe, it gives wings to the notion that he or she is arrogant, or has a hidden agenda, or both. Paradoxically, taking no risks is in itself a risk. The NDP took none.

Finally, Mulcair embraced the losing electoral strategy of Ontario NDP Leader Andrea Horwath and Toronto mayoral candidate Olivia Chow: he moved to the right. On deficits, on defence, on virtually any issue, the New Democrat leader didn’t sound like a traditional New Democrat. In his mad dash to get to the centre, he left behind his bewildered core vote, who accordingly wandered over to the more progressive Trudeau Liberals.

2. The Conservatives: Harperendum

In the days since Election 42, it has become conventional wisdom that the entire result can be reduced to a single cause: namely, that everyone hated Stephen Harper, and everyone voted to get rid of him.

As mesmerizing as this rationalization may be, it doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. The numbers tell the tale: the Conservative Party shed only 50,000 votes between 2011 and 2015. In percentage terms, they dropped by less than a single point. That is all.

While many Canadians may have professed to detest the departing Prime Minister, his core vote did not, and does not. Through serial scandals and assorted policy Vietnams, the one-third of Canadians who self-identify as Conservative did not give up on their man. Unlike progressive voters — who are highly promiscuous and flit, butterfly-like, between the Liberals, the New Democrats and the Greens — the Conservative bedrock remained with Stephen Harper.

Harper’s principal problem was that he was a Prime Minister who had been in power for a decade—and every prime minister becomes unpopular after a decade. Harper had held onto his loyalists, but he could not acquire new ones. In Election 2015, poll after poll registered the same result: only a miniscule number of voters indicated the Conservative Party was their second choice. To win again, Harper needed to grow his vote by six or seven more percentage points. But he could not, and did not. It ended his decade.

3. The Liberals: undersell, overperform

Justin Trudeau won, mostly, because he adopted Jean Chrétien’s well-known maxim: he undersold, but he over-performed.

In this regard, the Liberal leader was greatly assisted by his opponents. Their research had clearly shown them that Trudeau was seen by the electorate as too young and too inexperienced, and therefore a risk. The New Democrats and the Conservatives accordingly spent untold millions on ad campaigns to exploit this vulnerability.

In one extraordinary bit of political symmetry, the Tories and the Dippers came up with nearly-identical anti-Trudeau ad campaigns in virtually the same week in August. Just prior to the dropping of the writ, the Conservatives commenced aggressively promoting their ubiquitous “just not ready” theme about Trudeau — and the New Democrats debuted advertising stating that “Justin Trudeau just isn’t up to the job.”

The CPC and the NDP didn’t land on the same strategy by chance: their quantitative and qualitative findings had shown them it would hurt Trudeau. And, for a time, it did.

The “just not ready” and “just not up to the job” attacks also produced an unexpected result, however. They lowered expectations about Justin Trudeau so low that he could not help but exceed them. In debates, in media encounters, at rallies and on the hustings, Trudeau did far better than any of us had been led to believe he would. The campaign, which went on for week after interminable week, assisted him, too: he literally grew as a candidate within it. The Justin Trudeau who started the campaign was not the one who ended it.

Those, in the end, are the three most plausible explanations for what happened in Election 2015. The NDP tried to be something they weren’t; the Conservatives could not acquire new friends; and the Liberals were grossly underestimated.

There is no single, simple reason for the result in Election 2015.

But, for our purposes, three will suffice.

Adler-Kinsella show: historians will note that the sound cut out when Kellie Leitch’s name was mentioned

Did Trudeau’s Canada Post promise help him win the election?

As of today, the community mailbox insanity is on hold, thanks to Trudeau’s election victory.

And, two years ago, I thought it would sink the Harper Conservatives. Here’s what I wrote back then. Was I right?

“You’ve just lost the next election.”

The punk rocker who came in from the cold

Over on Facebook, Mark Marissen posted that he had been the subject of a U.S. diplomatic cable, published by Wikileaks. Cool, thought I. So I went to their searchable web site – and who knew they had a searchable web site? – and there I was. [Historians please note: I quit after Ignatieff dumped all of my friends. Canadians then went on to dump him – Ed.]

What is most amazing isn’t that I was named in a “top secret” missive. What is amazing is that grown-ups are actually paid to write this crap, and that they get to stamp “top secret” on it.

The world is crazy.