In Tuesday’s Sun: enjoy your convention, governing Harperites – it could be one of your last

Could Stephen Harper be taken down by the growing Senate scandal?

Sure he could. Of course he could. His poll numbers are dropping, his caucus is rebelling, and his trade-and-economy message is a fading memory. In recent days, he has looked simultaneously enraged and astonished that his authority is slipping away from him.

The fabled Conservative communications discipline is no more. Conservatives are attacking Conservatives, and caucus members are resisting Harper’s agenda. In political strategic terms, PMO is operating like a monkey with a machine gun.

The names of Mike Duffy, Pamela Wallin and Patrick Brazeau – once the stars of the Conservative fundraiser and talking head circuit – are now synonymous with scandal and sleaze, in perpetuity. They know it, and they’ve decided that, if they’re going down, they’re bringing all of their fairweather friends down with them.

Now, it is true that scandal stories get overplayed all the time. The Opposition, and those of us in the media, consider scandal to be far more important than the public does.

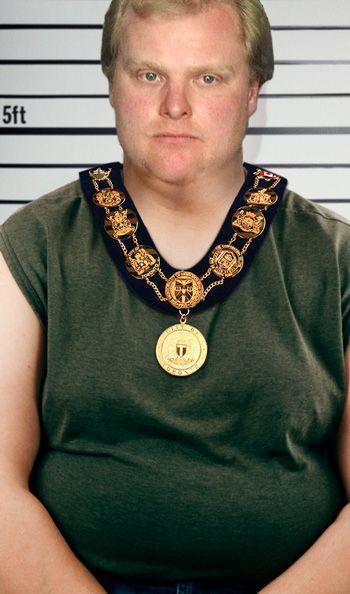

Case in point: Toronto mayor Rob Ford. Media report he smokes crack cocaine, he writes letters of reference on official letterhead for convicted criminals (one of them a murderer), and he regularly shows up to work after lunchtime. But, serial scandals notwithstanding, polls suggest his white angry male constituency remains (for now) with him.

Why should anyone think, then, that Harper’s Senate scandal – because it is now indisputably his, whether he was briefed by his senior staff or not – could fell him? Because, mainly, Harper is in the middle of a perfect storm. For some time, he was being buffeted by two storm systems – and then, to make matters appreciably worse, the Duffy-Wallin-Brazeau cyclone hit.

One the one side, Harper was losing support to the same thing that every government eventually faces: he was nearing the ten year mark. After a nearly decade in power, Canadians were wearying of him. His partisans were becoming less loyal – and his detractors had stopped merely disliking him, and were starting to hate him.

On the other side, Justin Trudeau appeared. Conservatives arrogantly and foolishly dismissed Trudeau’s appeal. They did not take seriously, even for a moment, the durability of the Liberal leader’s popularity with older Canadians (who still revere his father) and younger Canadians (who have been seduced by his undeniable charisma).

As Ipsos pollster Darrell Bricker has said to tin-eared Conservatives: “Trudeau is the real deal.” He is young, positive, energetic and progressive – in effect, he is the polar opposite of Stephen Harper. And he arrived when (see above) many Canadians were getting sick of Stephen Harper’s face.

That, then, is why the Senate scandal could indeed hasten the end of the Conservative Party’s time in government. Not because the scandal, in and of itself, is deadly. Because the scandal has come along at precisely the wrong time.

Politics, like comedy, is all about timing. For Stephen Harper’s fading Conservative regime, the timing of the Senate scandal could not possibly be worse.