Following tragedy, offering one’s “thoughts and prayers” on social media is commonplace. People now do it in a ritualized fashion whenever bad things happen.

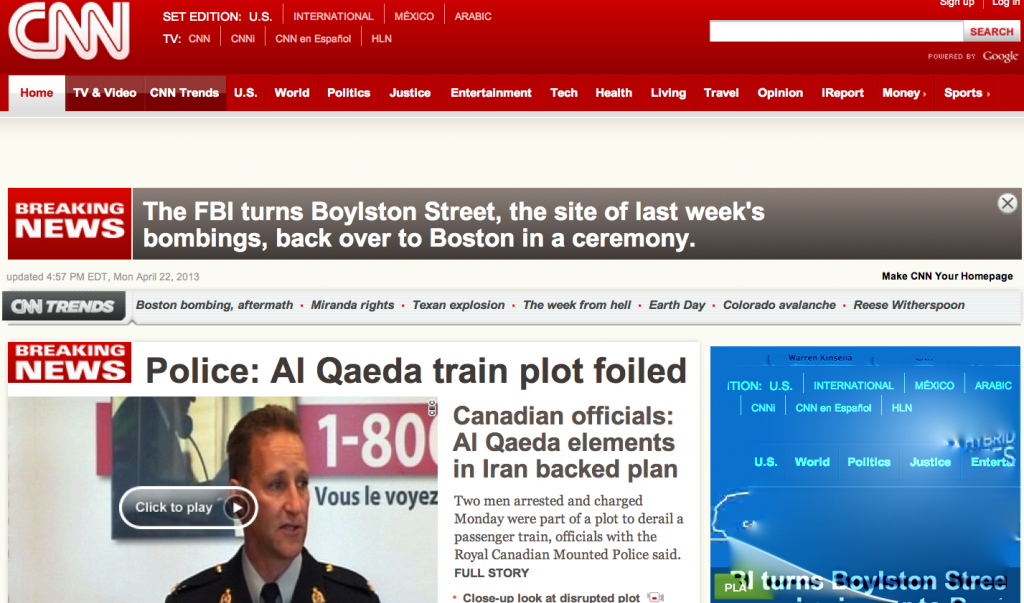

After the murders in Boston last week, average folks felt compelled to offer their “thoughts and prayers” to the victims, allegedly of the Tsarnaev brothers, on platforms like Twitter. And, after the Boston Marathon murders — after 9/11, after Newtown, after any number of other calamities — politicians offered up their thoughts and prayers, too. Most of what they had to say is as banal as it is meaningless.

But the media and their critics carefully scrutinize their words, to ensure that it carefully aligns with the mood of the moment.

Justin Trudeau learned this lesson the hard way last week. A couple hours after the Boston bombings, when emotions could not be higher, Trudeau sat down to a scheduled interview with the CBC’s Peter Mansbridge. The Liberal MP had won his party’s leadership the day before, so making the rounds with the TV networks was de rigueur. But, in Boston’s immediate aftermath, the encounter was fraught with peril.

Mansbridge’s first question about the attacks was as predictable as it was fair. As prime minister, “what do you do?”

Trudeau’s answer, as is now well known, was an unmitigated disaster: “First thing, you offer support and sympathy and condolences and, you know, can we send down, you know, EMTs or, I mean, as we contributed after 9/11? I mean, is there any material immediate support we have we can offer?”

That was uncontroversial, if communicated poorly (in all, Trudeau said “you know” nine times in a single answer). Then Trudeau got himself into big trouble. Instead of expressing outrage about the terrorist attacks and sympathy for the many victims, Trudeau chose instead to play amateur sociologist.

“At the same time, you know, over the coming days, we have to look at the root causes,” he said.

“… There is no question that this happened because there is someone who feels completely excluded, completely at war with innocents, at war with a society. And our approach has to be, OK, where do those tensions come from?”

Trudeau similarly went on for another 126 words, but the damage had been done.

Stephen Harper immediately seized on the Liberal leader’s words, as did much of the conservative-dominated commentariat, deploring Trudeau’s response as insufficiently tough and too bleeding heart.

It did not matter that Harper himself had said there is indeed a need to determine the root causes of terrorism.

As Maclean’s Paul Wells revealed, in 2011 Harper had given a speech on the National Day of Remembrance for Victims of Terrorism, pledging to find out “as much as we can about terrorists, their tactics, and the best solutions to protect people.”

That isn’t all that different from what Trudeau said, of course. But, much like his father would have done, Trudeau put reason ahead of passion. These days, in the social media era, passion always precedes reason.

Trudeau may not approve of that, but — having won his party’s leadership riding the crest of a social media wave — he should have known better.

He is unlikely to make that mistake again.

Comments (18)