Met some guy from Texas. Nice guy.

And, in case you were wondering, in conversation he was smart, perceptive and very funny. (Very.)

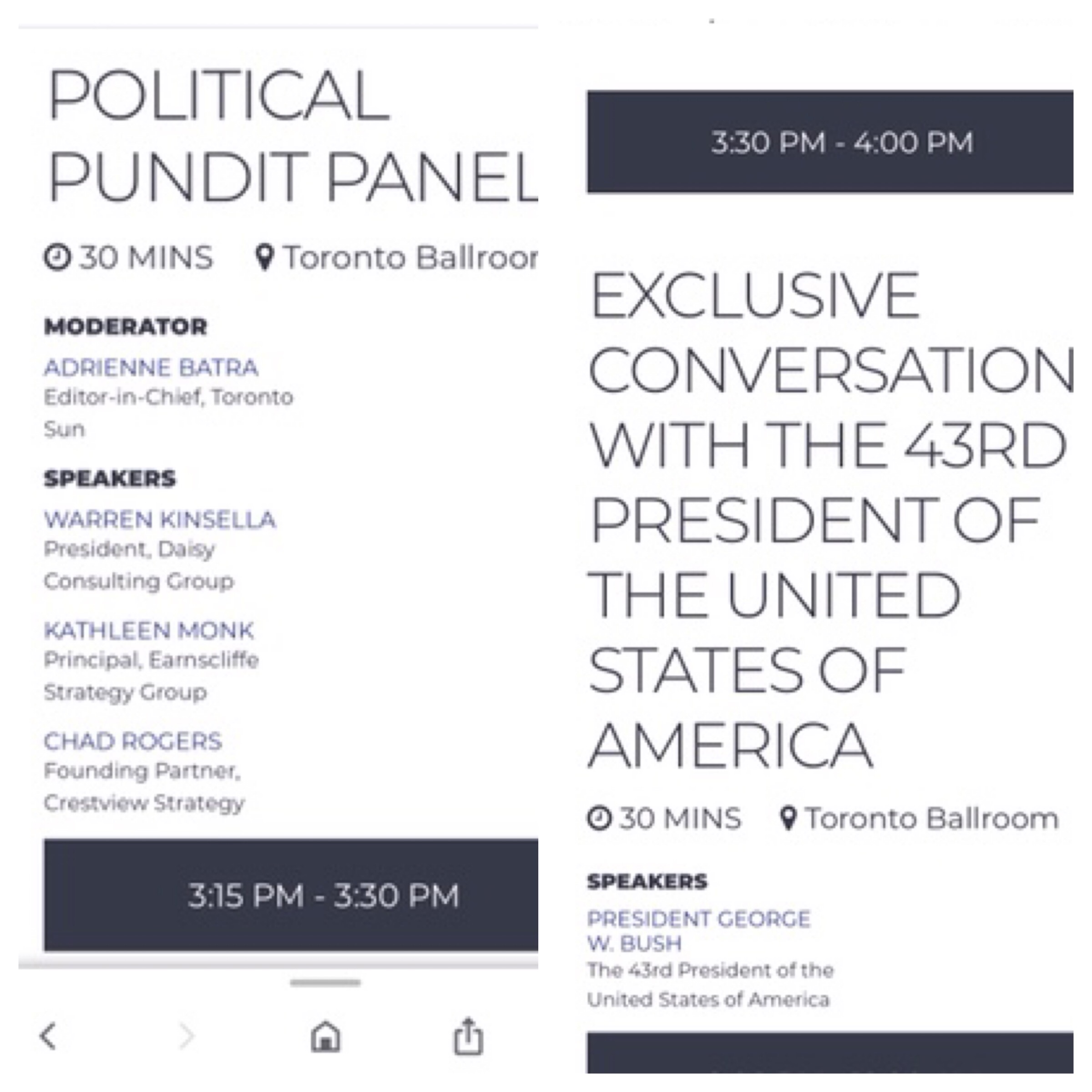

This picture was taken backstage at the OREA event (more pix here and here and here).

We talked, for just a minute, about Kennebunkport, and about how I’ve been going there for years with my kids and family and friends. He said he plans to start spending more time there himself.

Listening to him, I was reminded of what my former boss Jean Chretien told us, when we wondered about the White House reaction to our decision to not participate in the invasion of Iraq.

“He’s a very nice guy,” said the Canadian Prime Minister. “He’s always been a very nice guy.”

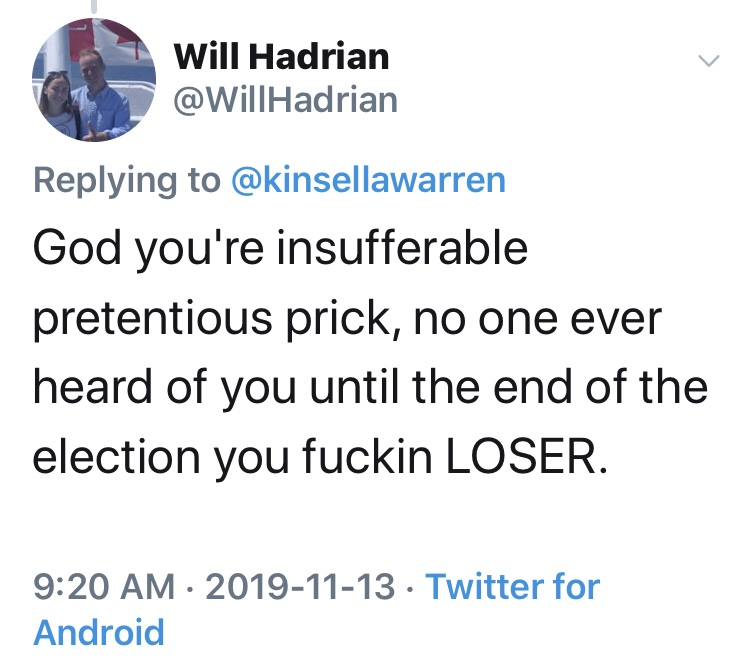

Caption contest!